It’s hard to put your finger on exactly why Angelmaker is one of the year’s best books, but then, it’s hard to put your finger on much of anything in Angelmaker, because it’s always in flux. One moment it’s an animated urban fantasy, the next nostalgic sci-fi with geriatric spies, and it’s no slouch in the between times either. Angelmaker takes in biting black comedy, heart-warming romance, some light crime monkeyshines, an incisive commentary on the state of play of people in power and power in people—in government around the world, if particularly in Britain—and so very much more that I’d have to be “mad as a shaved cat” to even attempt an account of it all.

So quantity, yes, and in every sense: in character as well as narrative, in wit and impact and ambition. But also quality. As one right-thinking English critic asserted, The Gone-Away World was “a bubbling cosmic stew of a book, written with such exuberant imagination that you are left breathless by its sheer ingenuity,” but for all its wonders, Nick Harkaway’s extraordinary debut was not without its issues in addition—foremost amongst them its madcap, almost abstract construction, which too often left one wondering what in The Gone-Away World was going on, even as it was going, going, gone.

Angelmaker, however, is a book far better put than its predecessor. A markedly more crafted artefact. Though the author’s roving eye remains intact, and those subjects its alights upon feel as delightful and insightful as ever, Harkaway has honed this incomparable trick of his to a filigree so fine that it appears nearly invisible; a filament of woven gold—impossible, yet a fact for all that—which runs through Angelmaker from the fanciful first to the beloved last.

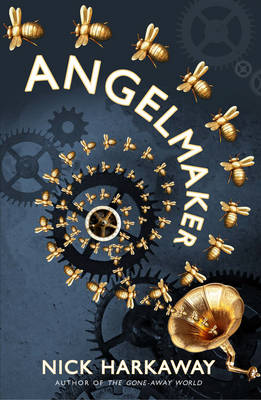

Not unrelatedly, it’s just such a thing that sets our tentative young protagonist off at the outset of Nick Harkaway’s new novel: a filament of woven gold, glimpsed in amidst “a Golgotha of armatures and sprockets” in an antique automaton, given to him by an crazy old crone to fix and finesse. After all, that’s what Joe Spork does for a living. He may be the only son of an infamous criminal, but Joe will be damned before he follows in his father’s hoosegow footsteps.

He shies away from the idea that he is what a certain class of crime novel calls an habitué of the demi-monde, by which it is implied that he knows gamblers and crooks and the men and women who love them. For the moment, he is prepared to acknowledge that he still lives somewhat on the fringes of the demi-monde in exchange for not having to talk about it.

Then again, “the stricture of Joe Spork is indecision, [as] a departing girlfriend once told him. He fears she was wrong,” and though he “tries not to reflect on the nature of a life whose high point is an adversarial relationship with an entity possessing the same approximate reasoning and emotional alertness as a milk bottle”—that being the stray cat that haunts his clockwork workshop—Joe is every inch an alumnus of the House of Spork. Once-mighty… now not so much. He’s smart and canny, connected and altogether too curious—bearing in mind what killed the kitty—so when several clients express an unhealthy interest in an objet d’art that has apparently passed through his hands, he simply can’t stop himself from looking into the thing.

The thing is, this doodah… it’s not just some high-value knickknack. It’s an apprehension apparatus; a vast and terrible truth-telling engine “whose shadow will be a block on the dreams of madmen; a weapon so awful that the world cannot survive its use, so that no one would use it save in the moment of their own inevitable destruction, and no one seek or allow the destruction of the one whose hand is on the hilt, lest they find the blade cuts every throat on Earth.” Long story short, it’s a doomsday device, and Joe isn’t the only person looking for it.

Meanwhile, “Edie Banister, ninety years of age and stalwart of the established order, has pushed the button on the revolution.” She’s the crazy old crone from before, of course, who set this whole show on the road, and she’s a side-splitting character in both concept and execution. In a stroke of sheer genius, Edie is also Angelmaker‘s secondary narrator. Initially, the time we spend in her rambunctious company feels—however hilarious—perhaps a little beside the point, recalling the most meaningless moments of The Gone-Away World, but this is easy to forgive when the intrigue-rich life and times Harkaway treats us to begins to tie in with the sordid history of the House of Spork, and almost entirely forgotten thereafter, when these alternating perspectives converge in an unforgettable eruption of nuns, Tupperware and homemade explosive.

Angelmaker exudes such zany exuberance from its every pore, taking frequent “flights of trenchant fantasy” which will not be to everyone’s tastes, but I beg you: don’t let the arch tone dissuade you from the text. Harkaway’s latest may not be the most self-serious genre novel ever written, but it’s elegant in its inanity, masterful in its make-believe, and though it is—make no mistake—absolutely barking mad, it’s also truly beautiful. Like the MacGuffin it revolves around, it stands to “uproot so many old and rotted trees,” and one must bear in mind that “there are men who have made their houses in them. There are men cut from their wood. All the bows and arrows in the world are made of [these trees],” and Angelmaker, appreciated from a certain standpoint, is a stout shield set against them.

As I was saying, it’s hard to put a finger on exactly why Angelmaker is one of the year’s best books. Know this, though: it is. If the apprehension engine only existed, I’m almost certain it would confirm my suspicions. Of course then we’d all overdose horribly on unfettered knowledge, so perhaps it’s for the good that we go ignorant of the odd thing.

Niall Alexander reviews speculative fiction of all shapes and sizes for Tor.com, Strange Horizons, Starburst Magazine and The Science Fiction Foundation. He also keeps an unapologetically bookish blog over at The Speculative Scotsman, and sometimes he Tweets, too.